- Home

- Wyl Menmuir

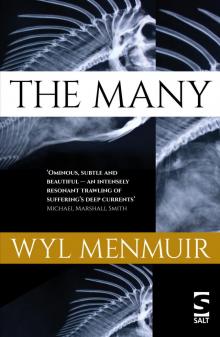

The Many

The Many Read online

The Many

Timothy Buchannan buys an abandoned house on the edge of an isolated village on the coast, sight unseen. When he sees the state of it he questions the wisdom of his move, but starts to renovate the house for his wife, Lauren to join him there.

When the villagers see smoke rising from the chimney of the neglected house they are disturbed and intrigued by the presence of the incomer, intrigue that begins to verge on obsession. And the longer Timothy stays, the more deeply he becomes entangled in the unsettling experience of life in the small village.

Ethan, a fisherman, is particularly perturbed by Timothy’s arrival, but accedes to Timothy’s request to take him out to sea. They set out along the polluted coastline, hauling in weird fish from the contaminated sea, catches that are bought in whole and removed from the village. Timothy starts to ask questions about the previous resident of his house, Perran, questions to which he receives only oblique answers and increasing hostility.

As Timothy forges on despite the villagers’ animosity and the code of silence around Perran, he starts to question what has brought him to this place and is forced to confront a painful truth.

The Many is an unsettling tale that explores the impact of loss and the devastation that hits when the foundations on which we rely are swept away.

‘Ominous, subtle and beautiful – an intensely resonant trawling of suffering’s deep currents.’ — MICHAEL MARSHALL SMITH

‘In this beautiful and frightening novel, Wyl Menmuir understands that loss is an enormous anchor from which everyone swings on the tide. His characters know they can never hoist this anchor, they only know they must try; otherwise the lifting lines become heavy chains dragging them to the bottom. The Many then captures the ecstasy observed on the faces of the drowning in the moment they surrender themselves to the sea.’ — MARK RICHARD, author of Fishboy

The Many

WYL MENMUIR was born in 1979 in Stockport. He lives on the north coast of Cornwall with his wife and two children and works as a freelance editor and literacy consultant. The Many is his first novel.

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

12 Norwich Road, Cromer, Norfolk NR27 0AX

All rights reserved

Copyright © Wyl Menmuir, 2016

The right of Wyl Menmuir to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

Salt Publishing 2016

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978-1-78463-065-2 electronic

1

Ethan

A THIN TRAIL OF smoke rises up from Perran’s, where no smoke has risen for ten years now. Ethan spots it close in, a few hundred yards from shore, as he scans the houses, a regularity of grey spirals where there should be a break in the line. He turns to see if Daniel has seen it too and shouts back at his wheelman to keep his eyes on the course until they’ve cleared the rocks and made land.

He’s as calm as he can be. He lowers his gaze and busies himself on the foredeck, kicking the empty creels and crates back into place and combing the nets laid highest for snags, waiting to feel the boat grounding through the soles of his boots.

Clem is waiting for them as they approach, knee-deep in water that could be a lake for all it is moving, holding the winch cable. He moves aside and shouts up to them a greeting or a curse that is drowned in the engine noise as Daniel brings the boat in too fast onto the beach. Ethan takes a step forward and steadies himself against the gunwale, fires a final insult at Daniel and throws a line over to Clem. By the time it has fallen into Clem’s hands, the winchman has secured it to the cable in a fluid motion and is climbing up out of the water towards the machinery.

The boat’s engine cuts out and the winch takes up the drone. Daniel doesn’t wait for Clem to bring the ladder as the Great Hope pauses beyond the wave line or even for the boat to clear the water. He throws his bag onto the beach and jumps down into the water before the winch takes up the slack. He walks up over the grey stones, bag slung across his back, and Ethan decides against calling him back to finish the job. There’s little enough to do and Daniel is right to want to be well away from him.

From where he stands on deck, Ethan looks past his wheelman at the smoke still rising from Perran’s place. Perran, who would wait at the window for first sight of the lights of the fleet, who would run down the beach and stare as the lights attached themselves to grey shapes and the grey shapes became boats. Perran, who coupled the boats to the winch, careful and slow, and as he did this, Ethan would look over the gunwales to see the thick brown thatch of hair on the boy’s head. Ethan’s fingertips trace unconsciously the smooth crisscross of railroad scar lines on his right arm.

‘Unnatural calm,’ Clem says, as Ethan climbs down the ladder.

So Clem has not noticed the smoke at Perran’s. Clem’s eyes are, as they should be, fixed on the horizon from the moment he arrives at the beach in the early morning, and he won’t look back towards his home until he’s re-launched the boats late on. Ethan takes up a guide pole and follows the Great Hope up to the flat, pushing it back on course as it grates its way across the stones.

Ethan’s is the first boat back and the others will limp in throughout the morning, all holds empty, he’s sure of that. There’s been no talk from the small fleet above the radio static. No talk until a catch is made. It’s a rule. Sure as not setting sail on a Friday is a rule, sure as talking low when you spot a petrel close in is a rule, sure as not moving into Perran’s is a rule.

He would like to say his father had taught him the rules, but the truth is he learned them mostly by observing them as his father and the other men in the fleet went about their business. His memory of his father is of being told over and again the seas will be empty before he’s old enough to take the helm and he remembers being told the story of a man who is cursed to fish an empty ocean for as long as he lives, the shore just in sight but never any closer. In spite of the direction he points the boat, the winds and tides conspire to push him away from the land. It’s one of the few stories he can remember his father telling. Aside from this oft repeated prophesy he recalls him mostly as a silence, sitting at the window until he cast off again, or poring over the arcana of his profession, charts marked with fishing grounds long past, charts that were scored heavy with notes, advice, warnings. When he was allowed out on shorter trips on days the sea was calm, they were marked by his father’s silence, by his insistence on silence.

In the wake of his father’s doom-heavy story, and the absence of any elaboration, the young boy had been left to dream of a bloody exodus of the sea. In this dream fish climbed, one silver back over another, out of the foam on stunted fins, limping and bleeding over the razored rock he limped and bled over himself gathering mussels and kelp. He had dreamt of fish in numbers he had never seen and never would see, beached, panting and piled in deep drifts, staring glass-eyed over a carnage of a haul. It turned out his father was wrong. The seas were as full as ever; it was the number of edible things in it that had changed was all.

There were still fish enough to catch back t

hen. Few and far between and hard fought over, even by the crews in the cove, but when the boats came in most times they carried catches up from their holds and there was a living to be made. There are pictures of them framed on the walls of the pub and in albums shut away in dresser drawers and in cupboards across the village. Grainy photographs of men sat on the sea wall smiling, gutting gurnard, dogfish, conger, turbot, and laying them out in neat rows in ice-filled crates. Ethan has come across them when he has searched for photographs of Perran, though he has found none, and it is hard sometimes now to bring to mind his face.

Four boats work out of the cove now. Dragged down the grey stones by Clem’s rusting skeleton of a tractor, and winched back up on their return. Four where there were fourteen. And the remains of the others corrode slowly, long since stripped of tackle and anything useful and waiting to be dislodged one by one in the winter storms and reclaimed by the sea.

In the early afternoon, four men converge outside the small café on the seafront.

‘You see the smoke up at Perran’s this morning?’ Tomas asks.

‘It’s emmets,’ says Rab. ‘Has to be. Who else’d move in there? No one who knew him.’

‘Have you seen them?’ asks Jory.

‘Him,’ says Tomas. ‘Him. Just one of him. Julie saw him arrive last night, late on, in a beat-up estate car he’s parked out back and then this morning he’s stood in the garden, just staring out like he owns the place.’

Rab looks across from over his mug of tea.

‘Been up for sale how long now?’ Tomas continues. ‘Looks like this time it stuck. Course it’s gone to an emmet.’

‘How long do you give him then?’ says Rab, but no one takes up the bet and they return to their drinks and to their own thoughts.

‘What’s with you then?’ Tomas asks Ethan. ‘Sore you’ve lost another wheelman? Maybe teach you not to be a shit to them, you ask me.’

Ethan looks at them across the table, finishes his drink and places the mug down as careful as he can. The others around the table shrug to each other as he shoulders his coat and leaves.

Ethan starts out along the sea road towards his house, but after a few steps turns back and instead winds his way up through the village to the highest row, to the houses almost at the tree line. There are lights on in many of them now, though when he gets to Perran’s there’s no sign of anyone there aside from the smoke that continues to rise from the chimney.

The first Ethan sees of Timothy Buchannan is a battered estate car parked on the grass behind the house, at an angle that leaves half a metre of the tailgate spilling over onto the track that runs behind the row of houses. He looks in through the windscreen, which is spattered with the evidence of a long drive. On the passenger seat is a disarray of plastic bags and part-eaten food, the crusts of a sandwich and crisps spilling out of their packets onto on a map, a cardboard coffee cup dribbling dregs onto the seat upholstery. A newspaper and a blue walking jacket are strewn across the back seats and the boot is full. He can see a toolkit and some cardboard boxes with food, cloths, sprays, bottles, piled in together as though the car was packed in a hurry.

It has been a long while since Ethan has come up this way, since he has stood outside Perran’s house. He walks around to the front of the house, stands at the door and listens, working out what he will say if he is confronted, but he can hear nothing from inside. The curtains are drawn, as they have been these ten years gone. Ethan walks away from the house and touches the car as he passes it, as though it might dissolve in the air like the smoke he had seen rising from the chimney.

The next day, Ethan motors out of the cove in a smaller boat he has dragged down the beach himself, and pulls up the pots on the fixed lines. It’s ritual rather than function. The pots always come up empty, though the rumours and predictions the fishermen spread among themselves in the village are still strong enough to keep him coming back. He does not bother to rebait them, but rinses out the old bait and checks each of the pots for damage before he drops them back over the side.

He finds he does not want to head back into the cove and have to confront the smoke rising up from Perran’s again, and instead of turning the boat back towards the village as he had planned, he steers a course along the coast for a mile or so, then heads out into open water, out towards the line of stationary container ships. The ships are spread out evenly across the horizon, as though they have lowered between them an enormous seine, an impossibly long net they are waiting to close. He cuts the engine back to a low growl and considers the line of ships for a few minutes. As he looks at them, he has the feeling of being hemmed in from all sides and a thought rises in him that he could break through the line of ships, that he could break one of the unspoken rules of the fleet. He supresses the thought, concentrating instead on the body of water in between the boat and the ships, looking for shadows in the water. He is close enough to the ships now to feel observed, though he cannot recall, even when they first arrived, ever having seen lights or any movement from the huge, rusting hulls. The men in the fleet ignore their presence as far as they can.

Ethan has been fishing for himself since he was twelve, and helming Great Hope since he was nineteen. With his thoughts still floating out by the container ships, looking through the wide gaps between the ships, he cuts the engine and opens the storage box at his feet. From within a tangle of netting, buoys and shackles, he pulls out a fishing rod, the one he used when his father first took him out on the boat. He threads a hook onto the line and baits the hook using some of the rotting meat he had not used to bait the pots and casts the line out. He braces the rod between the gunwale and his leg and rolls a cigarette.

‘I’m fine. I’m fine.’

Perran is still breathing out seawater from his mouth and nose and his hair is plastered in thick clumps against his head. Though there is no light on the shore, and what light there should be from the night sky is shrouded in a thick cloak of clouds, Ethan can see Perran is shivering beneath his jumper, which is now stuck fast against his chest.

‘I haven’t found him either. We need to go back. No point now, not in this.’

Ethan has to shout above the wind to make himself heard. Perran shakes his head and keeps on shaking it and there might be tears in his eyes, or it might be the salt water, or the rain. The wind, howling around them, is pushing him on.

‘He won’t be out along the rocks, or on the beach. Not in this. Go back to the house. I’ll go up on Lantern Street, see if he could have got up there,’ Ethan says. ‘Go home.’

Perran’s gaze follows the line of Ethan’s outstretched arm to where his dog may or may not be, and he turns his head back to look down the beach. It is mid-tide, though with the size of the waves and the height of them, it could be any tide. They can’t see the waves as they approach, just the final white crash as the swell collides with the stones on the beach and drags them back out through the cove’s entrance.

Perran pulls wet sleeves down over his hands and walks off in the direction of his house, though he turns back to look at the water several times. Ethan tries to conceal his concern, to reassure him.

‘I’ll find him, Perran, I will. Go on home.’

Ethan watches until Perran is out of sight and walks along the coast road to the turning up Lantern Street. The dog will already be back at Perran’s, he already knows that. The two of them will laugh when they see each other the next day, as though their search the night before had been a joke. Ethan will ruffle Perran’s hair and the fur on the back of the dog that was not lost all along.

He passes up by Perran’s house as he makes his way home. The house is in darkness and he assumes Perran has taken himself to bed, to be up for the boats.

In the morning, Ethan is woken by the sound of knocking at his door. After answering, and still thick with sleep, he dresses hurriedly and makes his way down to the beach, where he finds most of the boat crews standi

ng in a huddle by the winch house. A couple of boats have launched, but the rest are uneasy going out with no Perran there and no answer at his house. No matter how bad things are with the crews or the conditions, he is always there for the boats. Always.

Later in the morning, when still he does not appear, the fishermen organise themselves into search parties, Ethan among them, and they comb the beach and the empty sheds, and then walk up through the village calling for him. Ethan tells them about the events of the night before and they reassure him that Perran will turn up.

It isn’t the search party that brings news; it is one of the crews on the boats returning who calls it in. They see his yellow waders, bright against the rocks beyond the mouth of the cove, and call it through on the radio.

The operation to retrieve Perran’s body is a major one. The tide is on the rise again and the rocks are already part submerged. The same rocks make it difficult to get a boat close in and the cliffs are too steep, too unstable to descend. In the end, two of the men take a small rowboat out through the cove mouth. There isn’t much choice with the tide as it is, and Ethan watches with the others from the shore as the pair struggle against a sea still heavy, a hangover from the storm the night before.

When they bring Perran back in, they have covered him with a tarpaulin. The men on shore run forward and drag the boat up onto the beach and, when it comes to rest, one of the men pulls the tarpaulin back and Ethan sees he is curled up in the bottom of the boat like a child sleeping.

As the light starts to fade, Ethan reels his line back in and packs the fishing rod away. He pushes, from where they have been accumulating, a small mound of cigarette butts over the gunwale, and the congealed island of ash and paper bobs on the water and floats for a while before the waves start to break it down into its constituent parts. He looks out towards the container ships again, uncomfortable from looking down into the water for so long, and feels again the unfamiliar pull from beyond the ships and with it a dread he cannot place. He turns away from the ships and sets a course back towards the village.

The Many

The Many